Research Article

Improved Utilization of Resources as an Improvement of Outcome: the Effect of Multidisciplinary Team for Rectal Cancer in a District Hospital

Angela Maurizi* and Roberto Campagnacci

Department of General Surgery, Carlo Urbani Hospital, Italy

*Corresponding author: Angela Maurizi, Department of General Surgery, Carlo Urbani Hospital, Italy

Published: 26 Apr, 2017

Cite this article as: Maurizi A, Campagnacci R. Improved

Utilization of Resources as an

Improvement of Outcome: the Effect

of Multidisciplinary Team for Rectal

Cancer in a District Hospital. Clin Oncol.

2017; 2: 1267.

Abstract

Aim: Today, treatment decisions about patients with rectal cancer are increasingly made within

the context of a Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) meeting. The outcomes of rectal cancer patients

before and after the era of multi-disciplinary team was analyzed and compared in this paper. The

purpose of the present study is to evaluate the value of discussing rectal cancer patients in a multidisciplinary

team.

Methods: All rectal cancer patients diagnosed and treated in 2014-2015 in the General Surgery

Division of the “Carlo Urbani” hospital in Jesi (AN, Italy) were included. According to the national

guidelines, neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy should be administered to many rectal cancer patients.

Results: Sixty-five patients were included in this study: thirty patients in 2014 (pre-MDT) and

thirty-five patients in 2015. Improvements in the pathologic stage were seen in a rather big portion

of patients after the introduction of the MDT meetings, thanks to the increased adoption of the

neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy.

Conclusion: The vast majority of rectal MDT decisions were implemented and when decisions

changed, it mostly related to patient factors that had not been taken into account. Analysis of the

implementation of team decisions is an informative process in order to monitor the quality of MDT

decision-making.

Keywords: Rectal cancer; Multi-disciplinary team; Patient outcomes; Clinical stage; Pathological stage

Introduction

Rectal cancer represents a significant health care problem in terms of incidence, management complexity, and use of resources. Rectal cancer can have different patterns of presentation at diagnosis, which greatly influences both the prognosis and treatment choices. Treatment strategies vary depending on the level of the tumor, extension through the rectal wall in the mesorectum, presence of involved nodes inside and outside the mesorectum, presence of perforation, histological type and grade, and presence of distant metastases. The treatment of rectal cancer is extremely complex. The anatomy of the rectum presents a unique challenge and strict planes of dissection must be maintained to increase chances of healing. Basically, the management of rectal cancer has been changing over the past few decades, which has led to significant reductions in rates of local recurrence, increase in disease-free and overall survival, and reduction in permanent stoma rates [1]. However, surgical therapy is one aspect only of rectal cancer care. Treatment decision making for rectal cancer is challenging because of the inherent tradeoffs between effectiveness in terms of local recurrence and survival and functional outcomes in terms of bowel and sexual function [2-4]. This is further complicated by an increase in the number and type of available options for surgical treatment, as well as by changing paradigms for treatment based on response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Further complications are due to the importance of accurate preoperative staging, because under staging may result in primary surgery without neoadjuvant therapy, leading to increased risk of local recurrence, whereas over staging may lead to unnecessary radiotherapy and chemotherapy with poorer functional outcomes [5]. These various strategies in different combinations are aimed at improvement in care standards, improving quality of life with better local control and fewer complications, and improving survival. These decisions require communication between the surgeon, the pathologist, the radiologist, the medical oncologist, and the radiation oncologist. Indeed, the establishment of a multidisciplinary team to manage patients with rectal cancer attains just that. Further research has established the role of the pathologist and the radiologist in optimizing the multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer. Identification of tumor <1 mm from the circumferential resection margin proved to be a strong predictor of local recurrence, distant metastases, and survival, resulting in a new endpoint of rectal cancer treatment [6-9]. An optimal patient-tailored decisionmaking process requires adequate interdisciplinary communication and coordination. Hence, the complex treatment of rectal cancer requires a multidisciplinary approach [1,10-12]. To date, many studies have shown improvements in the standardization of care and an increased proportion of patients receiving this standard [13- 15]. Incorporating MDT into practice has resulted in an increase in the utilization of rectal cancer focused imaging, such as pelvic magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative clinical staging [16- 18], in the use of neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy [15,16,19] and in the accuracy and completeness of pathologic staging [16,19,20]. It is expected that immediate expert feedback from radiologists and pathologists will lead to improvements in the surgeon’s ability to achieve complete (R0) resection in a higher proportion of patients. Increasing complexity of multi-disciplinary management has led to the widespread adoption of the multi-disciplinary team meeting as a forum to direct treatment and improve quality of care [21,18]. In the past, rectal cancer treatment was primarily, and almost exclusively, surgical [22]. In fact, the notion that a multi-disciplinary approach improves medical management of cancer patients is becoming more prevalent. Many experts argue that the multi-disciplinary team approach presents a news standard of care, leading to a modern trend towards centralized and specialized centres for cancer management. Meaningful advances in imaging, staging, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and a growing arsenal of targeted therapies have all positively contributed to this notion. However, this multimodal approach demands for more time and resources, effective ongoing coordination between multiple specialties and can thus present formidable organizational challenges in a population where time can influence outcomes. There is some evidence that the introduction of rectal cancer MDT has improved outcomes for patients, but assessing the actual impact of MDT meetings is difficult, due to concurrent improvements in care brought in over time [19]. Ensuring that high quality treatment decisions are made requires discussion between experts in pathological and radiological data, information about patient related factors such as comorbid health status and patient treatment preferences and an effective decision-making process [23]. Rectal cancer treatment has become multi-disciplinary in nature involving at least surgeons, radiologists, radiotherapists, pathologists, and medical oncologists. This interconnection should commence at the time of the initial diagnosis. The preoperative handling of rectal cancer patients affects local recurrence and survival, and very often postoperative therapy schemes cannot compensate for any mistakes during the initial decision making. A multi-disciplinary team cans provide tailor-made treatment options for any given rectal cancer patient. Treatment out of the context of a MDT currently varies according to local dogma, facilities, and resources. In our hospital, before January 2015 patients with primary rectal cancer were initially examined by the surgeon who would assess the patient and make referrals at their discretion. There was no mandatory or formal review of the preoperative assessment or formal discussion of the patient among the surgeon, radiologist, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist. For the reasons stated above, our institution decided to set up a multi-disciplinary team to discuss every case of rectal cancer. The objective of this study is to evaluate the improvements on rectal cancer treatments outcomes after the introduction of the MDT meetings.

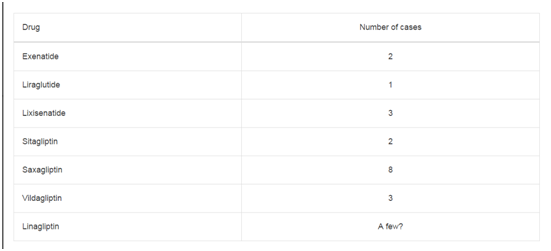

Table 1

Table 2

Table 2

Appropriate use of postoperative adjuvant chemo-radiation therapy

decreased over the study period down to 37% of MDT group patients.

Materials and Methods

Design of the study

In our health institute, weekly multi-disciplinary team conferences

were initiated in January 2015. Patients with newly diagnosed rectal

cancer being treated in our institution between January 1, 2015, and

December 31, 2015, were presented at a specific rectal cancer multidisciplinary

team. Patients were identified by the treating surgeon.

Patient identifiers were forwarded to the multi-disciplinary team

coordinator, who was responsible for drafting and distributing the

patient list at each multi-disciplinary team meeting. To the purpose

of this study, only patients with primary rectal cancer were included.

Then, the data from rectal cancer patients since year 2014 were

evaluated, before the adoption of multi-disciplinary team and since

the year 2015 after the adoption of meeting. Multi-disciplinary team

meetings were held every week and attended by surgeons, radiologists,

radiation and medical oncologists and key nursing personnel

treating patients hired at our center. A chair facilitated the work of

the multi-disciplinary team and the treating physicians presented

the clinical history, physical and endoscopic findings, and imaging

results for each patient. After this, the treating physician indicated

his/her proposed treatment plan. Complete datasets regarding

demographics, tumor stage, treatment, and outcomes based on

pathology after operation were obtained. During an MDT discussion

patient history, clinical and psychological condition, co-morbidity,

modes of work-up, clinical staging, and optimal treatment strategies

were discussed. These weekly meetings were used for discussion of

proper patient management, concurrently, among all appropriate

disciplines. A database was created to include each patient’ s workup,

treatments to date, and for recommendations by each specialty. We

analyzed 30 patients associated to the year 2014 and 35 patients

associated to the year 2015. ‘‘Demographic variables’’ consisted of age

at diagnosis, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, American Society

of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system (ASA

score), clinical stage and pathological stage. Other analyzed variables

included baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), the type of

imaging, use of neoadjuvant chemo-radiation, restaging following

neoadjuvant therapy, distance from the anal verge, operation type

and use of adjuvant chemo-radiation. ‘‘Outcome variables’’ consisted

in a comparison for each group between clinical and pathological

stage.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included Student t test of parametric variables

and chi-square test of proportions.

Results

There were 65 patients included in this study entered into the rectal MDT meetings at General Surgery Division of “Carlo Urbani” Hospital, Jesi, Ancona, Italy. These patients were split in MDT group (2015, no.35) and pre-MDT group (2014, no.30). Demographic data and their analysis are included in Table 1. The average age at diagnosis did not significantly differ between groups, as well as the variable “sex”. Comorbidities such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, body mass index, and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system did not differ significantly between groups. Preoperative clinical stages were similar between groups, except for that of clinical stage II, which was lower in the MDT group and statistically significant. Postoperative pathological stage did not differ between groups, except for that of clinical stage III, which was lower in the MDT group and statistically significant. Patients often arrive at our institution having completed their treatment, waiting for surgical operation only. The MDT did not exist before 2015. Baseline preoperative CEA measurement steadily increased, but did not reach significance. Colonoscopy and CT were high for both groups. Statistically significant increases were seen in the use of MRI but not for endoscopic rectal ultrasound to evaluate the depth of invasion. Complete metastatic imaging with CT to include imaging of the chest steadily increased. The majority of patients in the pre-MDT group included abdomen and pelvis imaging, but not chest. Proper neoadjuvant therapy was noticed to increase over time as did post-therapy preoperative restaging with MRI but they was no statistically significant difference. Appropriate use of postoperative adjuvant chemo-radiation therapy decreased over the study period down to 37% of MDT group patients (Table 2). Laparoscopic anterior rectum resection was performed in 18 patients in the MDT group and in 15 patients in the pre-MDT group.

Table 3

Table 3

As far as the outcomes we cannot verify the local and distant recurrence

because of the short follow-up of the 2 groups. But we can see (Table 3) that

thanks to the multi-disciplinary team and the increased use of the neoadjuvant

therapy, a statistically significant difference in reduction of the stage between the

clinical and pathological stage in the patients of the MDT group was verified, that

did not apply to the patients of the pre-MDT group.

Discussion

The multi-disciplinary team consists of primary team members

that include colorectal surgeons, radiologist, pathologist, oncologist,

meeting coordinator, and clinical nurse specialists. Other specialists

such as gastroenterologist, hepatobiliary surgeons, interventional

radiologist, clinical geneticist, stoma nurse, thoracic surgeon,

dietician, social worker, and research nurse are usually peripherally

involved. The meetings should occur weekly and be set up by the

team coordinator. Case notes, patient data, diagnostic data, staging,

and pathologic information should also be available during the

meeting. The cases to be discussed should include any new patient

with diagnosis of rectal cancer, all patients who have undergone

resection of a rectal cancer, patients newly identified with recurrent

or metastatic disease, and any other rectal cancer patients that

members of the team feel should be discussed. The clinical history

and imaging data in these patients are reviewed during meetings. A

radiologist reviews imaging with the team with particular focus on

operative planning. Also, histopathologic data are reviewed and in

many cases help to monitor the quality of surgery. Review of the raw

data serves to educate all members, gets all members well versed on

staging issues, and promotes the overall assessment and analysis of a

case. Postoperative cases are reviewed and the pathology is discussed.

In regard to rectal cancer, the pathologist provides valuable insight

into quality of total mesorectal excision which is reviewed grossly and

histologically. This can lead to an improvement in surgical technique.

The multi-disciplinary team accumulates information and opinions

so that management of decisions can be made on patient treatment. It

allows individualization of patient care so that care can be tailored for

any particular patient. Another key element of the multi-disciplinary

team is capturing the data on a database so that internal audits can

be performed to monitor outcomes. Improved coordination of care

and the opportunity to assess each patient from many viewpoints are

immediate benefits of a multi-disciplinary team. Multi-disciplinary

teams are typically associated with institutions with subspecialist

surgeons treating higher volumes of colorectal cancer patients. There

is growing evidence that high-volume colorectal cancer centers with

experienced subspecialty-trained surgeons have improved mortality

and have higher sphincter preservation rates [11,24-28]. Receiving

critiques or comments from experts in other fields can help surgeon

self-appraisal, specifically in reference to surgical margin review.

Audits of adequacy of total mesorectal excision with gross and

histopathologic review of the specimen can lead to improved surgical

technique [11,24]. Lately, an audit about the use of multi-disciplinary

team recommendations in Yorkshire, England, found out improved

survival in colon cancer patients treated with team recommendations,

and a trend toward increased survival in those with rectal cancer [19].

Inmulti-disciplinary team managed patients with rectal cancer, there

was an increased use of preoperative radiation and higher rates of

anterior resection. In our study, these decisions that changed after

any meetings were mainly due to patient co-morbidity that rendered

the recommended treatment as inappropriate or as not possible.

Other multi-disciplinary team decisions changed because they were

unacceptable to the patient. The high rate of implementation of

multidisciplinary team decisions recorded in this study suggests that

the colorectal multi-disciplinary team is an effective forum for making

management decisions that are acceptable to patients and can be

implemented. In this study, all the multi-disciplinary team decisions

that changed after a meeting resulted in final treatments that were more

conservative than originally planned. This highlights the need for up

to date information about the patient’s general health and preferences

to be available for the multi-disciplinary team meeting. Such

information might include relevant cardio respiratory or psychosocial

details. Information about patients’ preferences may also be difficult

to discuss routinely at meetings, either because patients may not have

particularly treatment wishes or because patients’ views frequently

evolve during the process of diagnosis and treatment [29]. Whichever

means is used to include more information about patient related

factors into multi-disciplinary team meetings, it is likely to require

investment, and evidence suggests that when patients are consulted

about the treatment decision, compliance is likely to be better [30,31].

For other cancers sites, it has been found out that MDT meetings

are useful in improving staging accuracy [32]. Recently a study has

shown that innovation in healthcare teams may reflect excellence

because it may mean that teams adapts to a changing environment

and increasing workload [33]. Others have shown that frequent and

voluntary interactions between team members increased opinion

sharing and ideas [23]. These are useful outcomes and it suggested

that by monitoring implementation of MDT decisions and studying

reasons why decisions change also provides useful clinical feedback

to teams. This process may also be a useful measure to peer review

the quality of MDT decision-making. This study suggests that there

is a need to develop pragmatic methods to allow the better inclusion

of information about co-morbidities and patient choice within MDT

meetings. If this could be achieved, it may lead to optimal treatment

decisions that can be subsequently implemented.

Multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer consists of accurate

imaging, meticulous surgery, and wise use of chemo-radiotherapy.

These elements are interconnected. Recently, Heald [34] proposed a

6-stage process for the management of rectal cancer after establishing

its diagnosis and excluding systemic disease. In the first stage, pelvic

MRI is performed, which provides the essential elements for the

preoperative decision making for rectal cancer. In the next stage, the

MDT discusses the patient’s case and the overall treatment plan is

formed. In stage 3, preoperative chemo-radiotherapy is administered,

when indicated. Selection for preoperative chemo-radiotherapy

principally is according to preoperative MRI. In the fourth stage, a

detailed precise surgical procedure is performed according to TME

concept. In stage5, pathologic audit of the specimen is performed

postoperatively. Finally, the case is evaluated thoroughly within the

MDT and decisions regarding postoperative treatment are made

along with surgical audit and feedback from the pathologists. The

MDT is responsible for choosing the tailor-made management for

all patients with rectal cancer and has to set up an algorithm for the

treatment of rectal cancer that is the backbone for any preoperative

decision making for colorectal cancer. The aim of the MDT is to

improve results and to offer state-of-the-art treatment. We consider

MDT discussion obligatory for all patients with rectal cancer.

The contribution of a MDT includes increased application of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, careful patients election for primary

tumor resection (decreased surgical mortality rate), and increased

resection of metastatic lesions in the liver.MDT could not only

increase the communication between surgeons, oncologists,

radiologists, and pathologists, which undoubtedly increased the

tumor resection rate, but also simultaneously decrease the number

of unnecessary surgeries and the surgical mortality, thanks to more

careful patient selection [35,36]. The evolution in the management of

rectal cancer in our center reflects international best practice and has

allowed us to examine the effect of multi-disciplinary management of

rectal cancer.

Conclusion

Multi-disciplinary team care of patients with rectal cancer has been shown to improve process and oncologic outcomes. The process requires full commitment from all involved in the care of rectal cancer patients. To sum up, a multi-disciplinary approach can assist in providing seamless coordination of care and is crucial to achieving improved outcomes. Our responsibility as colorectal surgeons treating rectal cancer patients is to understand and coordinate the wide variety of modalities available to optimize survival, minimize morbidity, and maximize quality of life for those with this strict disease. It should become the standard of care in the future.

References

- Dietz DW. Consortium for Optimizing Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRiCh). Multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer: the OSTRICH. J GastrointestSurg. 2013;17:1863-8.

- Sauer R, Fietkau R, Wittekind C, Rödel C, Martus P, Hohenberger W, et al. Adjuvant vs. neoadjuvant radiochemo therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: the German trial CAO/ARO/AIO-94. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:406-415.

- Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Putter H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:638-646.

- Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R. Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:811-820.

- Wright FC, De Vito C, Langer B, Hunter A. Expert Panel on Multidisciplinary Cancer Conference Standards. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a systematic review and development of practice standards. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1002-1010.

- Quirke P, Dixon MF. The prediction of local recurrence in rectal adenocarcinoma by histopathological examination. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:127-131.

- Quirke P, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Couture J, et al. Effect of the plane of surgery achieved on local recurrence in patients with operable rectal cancer: a prospective study using data from the MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG CO16 randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2009;373:821-828.

- Birbeck KF, Macklin CP, Tiffin NJ, Parsons W, Dixon MF, Mapstone NP, et al. Rates of circumferential resection margin involvement vary between surgeons and predict outcomes in rectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2002;235:449-457.

- Nagtegaal ID, Quirke P. What is the role for the circumferential margin in the modern treatment of rectal cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):303-12.

- Hervás Morón A, García de Paredes ML, Lobo Martínez E. Multidisciplinary management in rectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12(12):805-18.

- Jessop J, Daniels I. The role of the multidisciplinary team in the management of colorectal cancer. In: Scholefield JH, Abcarian H,Maughan T, eds. Challenges in Colorectal Cancer. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell 2006; 167–77.

- Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, Fouad MN, Harrington DP, Kahn KL, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992-6.

- Daniels IR, Fisher SE, Heald RJ. Accurate staging, selective preoperative therapy and optimal surgery improves outcome in rectal cancer: a review of the recent evidence. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:290-301.

- Quirke P, Morris E. Reporting colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2007;50(1):103-12.

- Chang KH, Smith MJ, McAnena OJ, Aprjanto AS, Dowdall JF, et al. Increased use of multidisciplinary treatment modalities adds little to the outcome of rectal cancer treated by optimal total mesorectal excision. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1275-83.

- Evans , Barton K, Rees A, Stamatakis JD, Karandikar SS. The impact of surgeon and pathologist on lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer and its impact on survival for patients with Dukes' stage B disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(2):157-64.

- Khani MH, Smedh K. Centralization of rectal cancer surgery improves long-term survival. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(9):874-9.

- Burton S, Brown G, DanielsIR, Norman AR, Mason B, Cunningham D. MRI directed multi disciplinary teampre operative treatment strategy: the way to eliminate positive circumferential margins? Br J Cancer .2006; 94(3):351-357.

- Morris E, Haward RA, Gilthorpe MS, Craigs C, Forman D. The impact of the Calman-Hine report on the processes and outcomes of care for Yorkshire's colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(8):979-85.

- Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, van der Worp E, Kapiteijn E, Quirke P, van Krieken JH, et al. Cooperative Clinical Investigators of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1729-34.

- Jessop J, Beagley C, Heald RJ. The Pelican Cancer Foundation and The English National MDT-TME Development Programme. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(l) 3:1-2.

- Dowdall JF, Maguire D, McAnena OJ. Experience of surgery for rectal cancer with total mesorectal excision in a general surgical practice. Br J Surg. 2002;89(8):1014-9.

- Catt S, Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Langridge C, Cox A. The informational roles and psychological health of members of 10 oncology multidisciplinary teams in the UK. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1092-7.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Colorectal Cancers: Manual Update. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2004.

- Rogers SO Jr, Wolf RE, Zaslavsky AM, Wright WE, Ayanian JZ. Relation of surgeon and hospital volume to processes and outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):1003-11.

- McGrath DR, Leong DC, Gibberd R, Armstrong B, Spigelman AD. Surgeon and hospital volume and the management of colorectal cancer patients in Australia. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(10):901-10.

- Purves H, Pietrobon R, Hervey S, Guller U, Miller W, Ludwig K. Relationship between surgeon caseload and sphincter preservation in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(2):195-204.

- McArdle CS, Hole DJ. Influence of volume and specialization on survival following surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91(5):610-7.

- Mallinger JB, Shields CG, Griggs JJ, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Rosenbluth RJ, et al. Stability of decisional role preference over the course of cancer therapy. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):297-305.

- Kelly MJ, Lloyd TD, Marshall D, Garcea G, Sutton CD, Beach M. A snapshot of MDT working and patient mapping in the UK colorectal cancer centres in 2002. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(6):577-81.

- Solomon MJ, Pager CK, Keshava A, Findlay M, Butow P, Salkeld GP, et al. What do patients want? Patient preferences and surrogate decision making in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1351-7.

- Stephens MR, Lewis WG, Brewster AE, Lord I, Blackshaw GR, Hodzovic I, et al. Multidisciplinary team management is associated with improved outcomes after surgery for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(3):164-71.

- Fay D, Borrill C, Amir Z, Haward R. West MA. Getting the most out of multidisciplinary teams: a multi sample study of team innovation in health care. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2006;79:553-67.

- Heald RJ. Surgical management of rectal cancer: a multidisciplinary approach to technical and technological advances. Br J Radiol. 2005;78 Spec No 2:S128-30.

- Amir Z, Scully J, Borrill C. The professional role of breast cancer nurses in multi-disciplinary breast cancer care teams. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8(4):306-14.

- Soukop M, Robinson A, Soukop D, Ingham-Clark CL, Kelly MJ. Results of a survey of the role of multidisciplinary team coordinators for colorectal cancer in England and Wales. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(2):146-50.