Case Report

Schwannoma Arising in a Lymph Node Mimicking Metastatic Pulmonary Carcinoma

Mitsuhiro Kamiyoshihara1*, Hitosi Igai, Fumi Ohsawa, Ryohei Yoshikawa, Munenori Ide and Masanori Iwashina

1Department of General Thoracic Surgery, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, Japan

2Department of Pathology, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, Japan

*Corresponding author: Mitsuhiro Kamiyoshihara, Department of General Thoracic Surgery, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, 3-21-36 Asahi- Cho, Maebashi, Gunma 371-0014, Japan

Published: 11 May, 2018

Cite this article as: Kamiyoshihara M, Igai H, Ohsawa

F, Yoshikawa R, Ide M, Iwashina M.

Schwannoma Arising in a Lymph

Node Mimicking Metastatic Pulmonary

Carcinoma. Clin Oncol. 2018; 3: 1456.

Abstract

Schwannomas commonly arise in the torso, extremities, and mediastinum. However, no interlobar

lymph node (#11i) lesions have ever been reported. This is a thought-provoking case, because it

involved a schwannoma arising in a lymph node mimicking metastatic pulmonary carcinoma. A

72-year-old man was diagnosed with primary pulmonary carcinoma, and 18F-Fluoro Deoxy Glucose

(FDG) positron emission tomography demonstrated high FDG uptake in the primary lesion and in

#11i, which suggested metastasis (clinical stage IIA). A right lower lobectomy with lymph node

dissection was performed. Fortunately, the enlarged #11i was a schwannoma and not metastasis. If a

schwannoma involved a mediastinal lymph node, it could alter the diagnostic process and therapy.

Keywords: Schwannoma; Lymph node metastasis; Lung cancer; Positron emission tomography

Introduction

Schwannomas are relatively rare neoplasms that arise from peripheral nerve sheath Schwann cells. The most common locations are the neck, head, extensor surfaces of the extremities, and posterior mediastinum [1,2]. Interlobar lymph node lesions are rare, and none have been reported in the English literature. This is the first report of a schwannoma arising in a lymph node mimicking metastatic pulmonary carcinoma. We present this thought-provoking case.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old man was referred to our hospital because of an abnormal shadow in the right lower lung on a chest X-ray. Computed Tomography (CT) showed an irregularly shaped, 27-mmdiameter, solid nodule with pleural indentation in the superior segment (segment 6) of the right lower lobe and a slightly enlarged interlobar lymph node (#11i) (Figure 1). The patient had been treated with methotrexate 8 mg/week for chronic rheumatoid arthritis for 10 years. The patient also had multiple neuromatoses and a resected skin schwannoma on his left leg. Levels of serum tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen, neuron-specific enolase, cytokeratin 19 fragment, and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide, were within the normal range. 18F-Fluoro Deoxy Glucose (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography (PET) showed high FDG uptake in the primary lesion in the right lower lobe [maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) = 6.5] and in the #11i lymph node (SUVmax = 2.7), suggesting metastasis (Figure 2). A trans bronchial lung biopsy from segment 6 led to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma with sarcomatoid components. These findings suggested a primary pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma, clinical stage IIA (T1bN1[#11i]M0). Pulmonary function tests revealed a vital capacity of 3.2 L (100%) and a forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 1.2 L (100%). Therefore, we performed a right lower lobectomy with hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. The operating time was 165 min, and blood loss was less than 50 g. Histologically, the tumor consisted of epithelioid and sarcomatous cells. The central tumor consisted of atypical cells in a solid growth pattern with necrosis. Atypical columnar epithelial cells in papillary or irregular glandular patterns were seen around the central tumor. Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse positivity for pan-keratin in the epithelioid and sarcomatous components. Consequently, a diagnosis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma was made (Figure 3). Histologically, the #11i lymph node contained spindle-shaped cells with pointed basophilic nuclei and nuclear palisading arranged in interlacing bundles. Neither malignancy of the proliferative cells nor invasion was observed. Immunohistochemically, the cells were positive for S-100 and negative for CD34 and SMA. These findings were compatible with schwannoma (Figure 4). The postoperative pathology indicated primary pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma (pT2a[pl2] N0M0, stage IB, complete resection). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 4. He underwent postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (two cycles of cisplatin plus vinorelbine), and as of 4 months post-surgery, the patient is alive without recurrence.

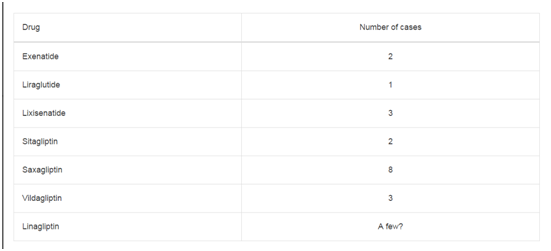

Table 1

Table 1

English-language studies on schwannomas detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography misdiagnosed as malignancies.

Figure 1

Figure 1

CT shows (A) a solid nodule in the right lung (white arrowhead)

and (B) slight enlargement of the interlobar lymph node (white arrowhead).

Figure 2

Figure 2

FDG-PET shows high FDG uptake in the right lower lobe (SUVmax =

6.5) and interlobar lymph node #11i, between the right middle and lower lobe

bronchi (SUVmax = 2.7) (black arrowhead).

Discussion

In this case, the use of FDG-PET failed to distinguish a

schwannoma from lymph node metastasis. A schwannoma arising

in an interlobar lymph node should be included in the staging

evaluation of primary lung cancer. However, we believe that it is

difficult to distinguish a schwannoma in an interlobar lymph node

from metastasis. There are several reports [3-5] of schwannomas

misdiagnosed as lymph nodes metastasis or malignant tumors

detected by FDG-PET (Table 1) shows that the SUVmax values of

schwannomas range from 2.7 to 5.6, depending on the degree of

cellularity. They have a characteristic dual pattern with areas that are

highly (Antony A) and less (Antony B) cellular, and the degree of

cellularity varies widely among lesions; therefore, these tumors can

display a wide range of SUVs (0.33-3.7 and 1.9-7.21, respectively)

[6,7]. Consequently, FDG-PET is not always useful for differentiating

benign from malignant tumors. Retrospectively, the SUVmax of the

#11i lymph node was too low compared with that of the primary

lesion to diagnose it as malignant. However, our criterion for a

positive SUVmax is greater than 2.5; therefore, we diagnosed the #11i

lymph node as malignant. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is

potentially a more useful method for detecting a schwannoma in a

lymph node. On T1-weighted images, the masses are homogenous

and isointense relative to skeletal muscle, while T2-weighted images

reveal hyper intense masses and strong enhancement [8]. However,

MRI of the chest is not always performed routinely in the evaluation

of primary lung cancer. In our patient, surgery was indicated because

of the interlobar lymph node involvement. However, if a mediastinal

lymph node is involved in a schwannoma, the patient should undergo

preoperative mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound-guided

transbronchial needle aspiration. This could alter the diagnostic

process and therapeutic modality completely, depending on the

location of the lymph node involvement.

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma is a rare primary malignancy

that possesses carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. Pleomorphic

carcinoma generally follows an aggressive clinical course and tends to

grow rapidly and invade adjacent structures during the early stage

[9]. This knowledge led us to diagnose the #11i lymph node as a

metastasis from the primary lesion. In summary, we report the first

case of a schwannoma in an interlobar lymph node. We learned a

lesson from this case. We should have considered that a patient with

multiple neuromatoses tends to have schwannomas throughout the

body.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Histologically, the tumor cells have a biphasic appearance with

epithelioid and spindle cell sarcomatous components (hematoxylin and eosin

staining; magnification, × 400). Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma with

adenocarcinoma components was diagnosed.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Histologically, the #11i lymph node reveals a schwannoma

composed of spindle-shaped cells with nuclear palisading arranged in

interlacing bundles (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification,

×100).

References

- Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, Hjdu SI. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilenomas). Cancer. 1969;24(2):355-66.

- Uchida N, Yokoo H, Kuwano H. Schwannoma of the breast: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35(3):238-42.

- Ortega-Candil A, Rodríguez-Rey C, Cabrera-Martín MN, García GarcíaEsquinas M, Lapeña-Gutiérrez L, Carreras-Delgado JL. 18FDG PET/CT imaging of schwannoma mimicking colorectal cancer metastasis. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2013;32(5):332-3.

- Fujii T, Yajima R, Morita H, Yamaguchi S, Tsutsumi S, Asao T, et.al. FDGPET/CT of schwannomas arising in the brachial plexus mimicking lymph node metastasis: report of two cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:309.

- Igai H, Kamiyoshihara M, Kawatani N, Ibe T, Shimizu K. Sternal intraosseous schwannoma mimicking breast cancer metastasis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:116.

- Beaulieu S, Rubin B, Djang D, Conrad E, Turcotte E, Eary JF. Positron emission tomography of schwannomas: emphasizing its potential in preoperative planning. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(4):971-4.

- Benz MR, Czernin J, Dry SM, Tap WD, Allen-Auerbach MS, Elashoff D, et al. Quantitative F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography accurately characterizes peripheral nerve sheath tumors as malignant or benign. Cancer. 2010;116(2):451-8.

- Beaman FD, Kransdorf MJ, Menke DM. Schwannoma: radiologic— pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1477.

- Fishback NF, Travis WD, Moran CA, Guinee DG Jr, McCarthy WF, Koss MN. Pleomorphic (spindle/giant cell) carcinoma of the lung. A clinicopathologic correlation of 78 cases. Cancer. 1994;73(12):2936-45.