Research Article

Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Appendix in Adolescents and Young Adults

Grace Onimoe1*, Eric Kodish1 and Richard Herman2

1Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Cleveland Clinic Children’s, Cleveland Ohio, USA

2Division of Pediatric Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Children’s, Cleveland Ohio, USA

*Corresponding author: Grace Onimoe, Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Cleveland Clinic Children’s, Cleveland Ohio, USA

Published: 28 Jul, 2017

Cite this article as: Onimoe G, Kodish E, Herman R.

Neuroendocrine Tumors of the

Appendix in Adolescents and Young

Adults. Clin Oncol. 2017; 2: 1318.

Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors involving the appendix in young people are uncommon. A retrospective review of appendiceal NET at Cleveland Clinic Children’s was completed, 14 patients were identified, 3 cases were classified as intermediate grade tumors, lymph node metastasis was present in 2 cases. The largest size tumor measured 4.5 cm, 5 patients underwent right hemicolectomy per NANETS criteria, 3 patients who met this criteria did not undergo hemicolectomy. No disease recurrence. Appendiceal NET is associated with an excellent prognosis in localized disease and has low metastatic potential. A multicenter review will be beneficial in better defining criteria for a second surgery.

Abbreviations

RHC: Right Hemicolectomy; NANETS: North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society; NET: Neuroendocrine Tumor; PT: Patient; AYA: Adolescents and Young Adults; RX: Treatment; LN: Lymph Node; PT: Patient; NO: Number

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) are rare in the pediatric population and originate from the

neuroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract, the appendix being the most common site.

A summary of existing series reports an incidence between 2 and 5 per 1000 cases in pediatric

appendectomies [1]. Despite their low incidence, NET represent the most frequent tumor involving

the gastrointestinal tract in children and adolescents [2-4].

Most appendiceal NET are incidental findings in a post-appendectomy specimen and therefore

have no characteristic tumor-specific symptoms. Clinical presentation of appendiceal NET is similar

to acute appendicitis, but it can be an incidental intra-operative finding during appendectomy or

other surgical procedures [5].

The metastatic potential depends on the size, depth, and site of the tumor [6].

We reviewed our institutional experienceconcerning treatment and outcomes and compared to

current NANETS guidelines.

Methods and Results

We performed a retrospective review of adolescent and young adult (age 15-23) patients

diagnosed with appendiceal NETbetween January 2010 to May 2016. Data which included

demographics, presenting symptoms, mode of imaging, pathologic review, disease workup,

treatment, post treatment surveillance were collected and analyzed, 14 patients were identified as

diagnosed with appendiceal NET (Table 1). Females were in the majority (9/14). The most common

presenting symptom was abdominal pain.

All patients underwent appendectomy, withpost-operative diagnosis from pathology

examination. Mean age at diagnosis was 17.2 years (age 15-23 years), 5 patients underwent right

hemicolectomy with indications being tumor size >2 cm, perineural invasion and lymph node

metastasis; PT 2 TS 4.5 cm, tumor invasion, LN involvement; PT8 TS 2 cm, Grade 1, No invasion

/LN involvement, PT 9 TS 1.8 cm, no invasion, positive LN, PT 11 TS 0.4 cm, Grade 1, Perineural

invasion, No LN involvement and PT 14 with tumor size of 3 cm.

PT 7 had TS >2 cm while patient 12 TS could not be determined, both did not undergo RHC;

and are alive and well at follow-up periods of 36 months and 14

months respectively.

Overall, tumor size ranged from microscopic foci to 4.5 cm, 2

patients had metastatic disease involving the regional lymph nodes

only and 1 patient had lymphovascular involvement (Table 1). The

patients with lymph node involvement had additional findings of

mesoappendix involvement (PT 2) and intermediate grade (PT 9),

3 patients had intermediate risk disease per NANETS consensus

guidelines for the diagnosis and management of NET, 1 patient

had a perforated appendix; patient did report flushing and diarrhea

occurring prior to presentation (15 year old female who presented

with 4 days of vomiting, diarrhea, occasional flushing with shivering

& intermittent fever and abdominal pain).

This patient was found to have regional lymph node involvement

and underwent right hemicolectomy.

Post-surgery surveillance included imaging utilized CT abdomen

more commonly, octreotide scan, Chromogranin A and 5 HIAA.

Follow-up duration ranged from 2 – 77 months (median = 12

months). Relapses did not occur.

Table 1

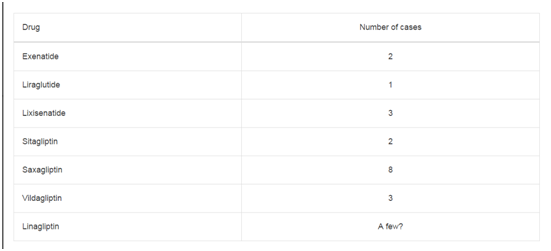

Table 2

Table 2 Surgical Approaches from NANETS consensus guidelines for the management of well differentiated NETs of the Appendix [7].

Discussion

The first case of an appendiceal NET was described by Berger in

1882, but it was not until 1907 that the term karzinoid was coined by

Sigfried Oberndorfer at the German Pathologic al society Summit in

Dresden ([7]).

Appendiceal NET represent tumors with a low metastatic

potentialand in the majority of patients, surgery is curative.Majority

in children arise in the appendix; however they can also occur in other

primary sites including the small intestine, bronchus and others [8,9].

These lesions are more likely to be found in females, as reported

in several publications [6,10].

Classic carcinoid syndrome which consists of some combination

of wheezing, flushing, diarrhea, hypotension and /or abdominal pain

is rare in young patients with NETas they rarely have metastasis to the

liver or other sites ([7]).

Incidence at our institutions concurs with the rare occurrence of

this tumor in pediatric patients.

Carcinoid syndrome occurrence was rare (1/14); abdominal pain

in contrast was 100% (14/14).

Majority of patient (10/14) had low grade tumors with tumor size

being less than 2 cm.

Pediatric management of NET is derived from an adult medicine

based guideline- The NANETS guidelines [11] which is elaborated

in Table 2: small (<1cm) well differentiated carcinoids confined to

the tip of the appendix that are excised are considered cured if there

is no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or invasion into the

mesoappendix, and do not require any follow-up; <2 cm tumors

(without regional involvement) also do not require any follow up.

Right hemicolectomy is being recommended for appendiceal NET

with evidence of tumor invasion at the base of the appendix, in

patients with tumors greater than 2 cm, in those with tumor where size

cannot be determined, incompletely resected tumors, intermediate to

high grade tumors, evidence of lymphovascular invasion, invasion of

the mesoappendix, and mixed histology, 5 patients underwent right

hemicolectomy; PT 2 TS 4.5 cm, tumor invasion, LN involvement;

Patient 8 TS 2 cm, Grade 1, No invasion/LN involvement, PT 9 TS 1.8

cm, intermediate grade, PT11 TS 0.4 cm, Grade 1, lymphovascular

invasion and PT 14 with tumor size of 3 cm.

Interestingly PT 7 had TS >2cm while PT 12 TS could not be

determined, both did not undergo RHC; and are alive and well, 6

patients did not meet criteria for RHC and appropriately did not

undergo surgery. Of the five that underwent RHC two patients had

positive regional lymph nodes.

Three patients who meet NANETs criteria for RHC did not

undergo further surgery (Patient 7, 10, 12); and remain alive/disease

free with a total combined follow-up duration of 41.5 months. Our

report is limited by number of patients and duration of follow up.

A multicenter review will be beneficial in better defining criteria

for a second surgery in AYA.

Disease workup after diagnosis and surveillance in our institution

consisted of computed tomography abdominal & lung scans,

Octreotide scans, Chromogranin levels and 5-HIAA levels.

Follow up schema has been difficult to standardize, generallywe

have recommended proposed NANETS guidelines of reassessment

between 3 and 6 months after complete resection; and every 6 to 12

months for at least 7 years.

Our report adds to existing literature to pediatric patients with

appendiceal NET and regional lymph node metastases [12-15].

In conclusion,a larger patient series is needed to better define

which patients with appendiceal NETs will benefit most from

undergoing a right hemicolectomy.

Acknowledgement

Dr Peter Anderson of the department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Cleveland Clinic Children’s for reviewing manuscript.

References

- Doede T, Foss HD, Waldschmidt J. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children--epidemiology, clinical aspects and procedure. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 10(6): 372-377.

- Hatzipantelis E, Panagopoulou P, Sidi-Fragandrea V, Fragandrea I, Koliouskas DE. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children: experience from a tertiary center in northern Greece. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010; 51(5): 622-625.

- Corpron CA, Black CT, Herzog CE, Sellin RV, Lally KP, Andrassy RJ. A half century of experience with carcinoid tumors in children. Am J Surg. 1995; 170(6): 606-608.

- Parkes SE, Muir KR, al Sheyyab M, Cameron AH, Pincott JR, Raafat F, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children 1957-1986: incidence , treatemnet and outcome. Br J Surg. 1993; 80: 502-504.

- Vani BR, Thejaswini MU, Kumar BD, Murthy VS, Geethamala K. Carcinoids of the appendix in children: a r eminder. Case Rep Clin Pract Rev. 2003; 4(2): 69-72.

- Neves GR, Chapchap P, Sredni ST, Viana CR, Mendes WL. Childhood carcinoid tumors: description of a case series in a Brazilian cancer center. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006; 124(1): 21-25.

- Dall'Igna P, Ferrari A, Luzzatto C, Bisogno G, Casanova M, Alaggio R, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the appendix in childhood: the experience of two Italian institutions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005; 40(2): 216-219.

- Howell DL, O'Dorisio MS. Management of neuroendocrine tumors in children, adolescents, and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012; 34 Suppl 2: S64-S68.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003; 97(4): 934-959.

- Spunt SL, Pratt CB, Rao BN, Pritchard M, Jenkins JJ, Hill DA, et al. Childhood carcinoid tumors: the St Jude Children's Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35(9): 1282-1286.

- Boudreaux JP, Klimstra DS, Hassan MM, Woltering EA, Jensen RT, Goldsmith SJ, et al. The NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the Jejunum, Ileum, Appendix, and Cecum. Pancreas. 2010; 39(6): 753-766.

- Kim SS, Kays DW, Larson SD, Islam S. Appendiceal carcinoids in children--management and outcomes. J Surg Res. 2014; 192(2): 250-253.

- Cernaianu G, Tannapfel A, Nounla J, Gonzalez-Vasquez R, Wiesel T, Tröbs RB. Appendiceal carcinoid tumor with lymph node metastasis in a child: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2010. 45(11): e1-e5.

- Volpe A, Willert J, Ihnken K, Treynor E, Moss RL. Metastatic appendiceal carcinoid tumor in a child. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000; 34(3): 218-220.

- Pelizzo G, La Riccia A, Bouvier R, Chappuis JP, Franchella A. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children. A report of 25 cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1977; 143(3): 173-175.