Research Article

Physical, Emotional and Spiritual Well-Being, Dignity and Hope in Adult Patients with Solid and Hematologic Malignancies, on Cure or Follow-Up

Carla I Ripamonti1*, Loredana Buonaccorso2, Alice Maruelli3, Guido Miccinesi4

1Oncology-Supportive Care in Cancer Unit, Department Onco-Ematology, Fondazione IRCCS, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Italy

2AMO, Association of Oncological Patients from nine towns and villages located in the Northern area of Modena, Italy

3Psychology Unit, LILT and Center for Oncological Rehabilitation-CERION of Florence, Italy

4Clinical Epidemiology Unit, ISPO-Institute for the Study and Prevention of Cancer, Florence, Italy

*Corresponding author: Carla Ida Ripamonti, Oncology- Supportive Care in Cancer Unit, Department Onco-Ematology, Fondazione IRCCS, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Italy

Published: 26 Apr, 2017

Cite this article as: Ripamonti CI, Buonaccorso L, Maruelli

A, Miccinesi G. Physical, Emotional

and Spiritual Well-Being, Dignity and

Hope in Adult Patients with Solid and

Hematologic Malignancies, on Cure or

Follow-Up. Clin Oncol. 2017; 2: 1268.

Abstract

Introduction: In oncological setting, the assessment of physical/emotional symptoms and above all

of existential/religious needs and resources, hope and dignity are rarely performed in the routine

clinical practice. Moreover, comparative assessments of patients with Solid Cancers (SC) vs. those

with Haematological Malignancies (HM) are lacking.

Patients and Methods: We analyzed data collected in 2 similar cross-sectional studies of consecutive

patients with SC or HM on cure or follow-up regarding the presence and intensity of physical/

emotional symptoms, religious needs and resources, level of hope and dignity–related distress. We

used the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), System of Beliefs Inventory (SBI_15R),

Hert Hope Index (HHI) and Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI).

Results: 289 patients with SC and 169 with HM were involved with a mean age of 61 and 58 years

respectively (p=.012); 56% of patients with HM vs. 43% with SC were male (p=.009). KPS ≥80 was

above 90% in both groups, and 49% of the HM as well as the SC patients were on active treatments;

18% of the HM patients had received psychological support vs. 29% SC patients (p=.007). No

significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding physical/emotional

symptoms, dignity – related distress and the presence of hope, whereas religious resources were

higher among patients with solid cancer (p=.036). Among HM patients, in comparison with the

phase of diagnosis hope score was significantly lower during the treatment phase (-3.3; 95% CI: -5.6;

-1.0), and in case of relapse/metastases (-6.6; 95% CI: -11.6; -1.6).

Conclusion: SC and HM patients don’t differ much in their physical, emotional and spiritual needs,

even if HM patients seem to be more vulnerable to losing hope as the disease progresses. More

important, HM patients may lack sufficient patient support.

Keywords: Physical/emotional symptoms; Existential/religious needs/resources; hope; Dignity related distress; Solid cancer; Haematological malignancies

Introduction

The World Health Organization suggests the Health Care Professional to perform

multidimensional evaluations of the presence and intensity of emotional and physical symptoms

in cancer patients starting from the diagnosis [1], because early identification of suffering due to

cancer and its treatments can be addressed at the earliest opportunity and when necessary referred

to specialists. The psychosocial domain should be integrated into the routine cancer care to improve

the possibility of cognitive and emotional processing for the patients and also for their families [2]. Scientific evidence exists to recommend supportive psychotherapy as a valid therapeutic intervention

[3]. It is often recommended a two-phase process for the assessment of the psychological unmet

needs, as a case at the screening through standardized tools identifies the level of symptoms (above a

certain cutoff) without providing a diagnosis [4]. Although data of the literature have demonstrated

the utility of simple screening tools to assess the symptoms and to activate the specific services, as

support therapies to manage pain and toxicities, psychological support [4,5] and group therapy [6,7], the routinely assessment of the symptoms and the needs, the

dignity-related distress, the resources (religiosity, hope) of the patients

undergoing oncological therapies with curative or palliative intent or

during follow-up period both in patients with solid cancer or with

hematological malignancy is still few. One possible explanation is the

lack of proper education in symptom assessment and management

and the lack of simple, not time consuming, validated in the own

language, assessment tools to use in the daily clinical practice in a

context of a structured conversation. Further difficulties come from

the lack of adequate training in communication skills and processes

for health professionals [8,9]. A recent Italian study showed that

the cancer patients that used complementary therapies reported

more unmet needs about the quality of the relationships with health

professionals [10].

A revision of the literature extracted from 21 multi-national

studies in a pooled sample of 4,067 patients with solid or haematological malignancies undergoing active cancer treatments

and assessed by means of different assessment tools, showed that the

most prevalent symptoms were fatigue, irritability, disturbed sleep,

outlook, unspecified pain, dry mouth, anorexia/appetite changes,

dyspnea, difficulties in concentration/remember, numbness tingling,

bowel changes, nausea, dizziness, dysphagia, sexual dysfunction,

nocturia [11]. Contrary to data reported in the past literature, also the

haematological patients refer physical and emotional distress during

all phases of disease [12-14]. In particular leukemia patients may

suffer from moderate and sever physical pain and emotional distress,

depression and hopelessness during all clinical phases [15,16].

However comparative data are not available on the differences

between the presence and intensity of the symptoms in the two

groups of patients with SC or HM. The aim of this study is to compare

the patients with solid and haematological malignances on cure or on

follow-up, in order to investigate the differences in prevalence of the

patients reported physical and emotional symptoms, dignity-related distress, religious needs and resources such as hope.

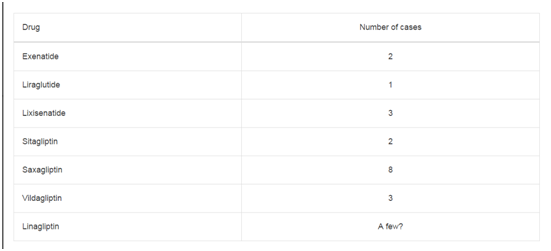

Table 1

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristic of patients with Solid Cancer (SC) and Haematological Malignancies (HM). Mean value and (DS), or N and (column %).

Table 2

Table 2

Physical and emotional symptoms (moderate/severe), and religious needs/resources in patients with Solid Cancer (SC) or Haematological Malignancies (HM).

Mean value and (DS), or N and (column %).

Patients and Methods

Patient population

In this study we report a secondary analysis of two different

cross-sectional studies, conducted in 2012 and 2014 respectively,

with the same methodology. The patients enrolled were cared

for by Supportive Care in Cancer Unit of Fondazione IRCCS,

Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori of Milan, and Centre of Oncological

Rehabilitation-LILT, CERION of Florence. The inclusion criteria

were: 1. Age >18 years; 2. Ability to read and speak Italian; 3. On

active oncological treatments or in follow-up; 4. Life expectancy >6

months; 5. Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥70; 6. No severe

symptoms which could cause discomfort during the compilation of questionnaires; 7. Outpatients; 8. Written informed consent. Patients with signs/symptoms of cognitive impairment were excluded from

the study.

By means of a questionnaire ad hoc, basic information was

collected comprising of age, gender, civil status, education,

employment, religiousness (churchgoer, believer non churchgoer,

non-believer), Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), clinical

variables including phase of the disease (diagnosis/treatment, follow

up/rehabilitation, metastasis/relapse), primary tumour, oncological

treatment received in the last 3 months, previous referral to a

psychologist. Approval was obtained from the ethics committees

of the participating centers. Measures Of all patients, we analyzed

the presence and intensity of physical and emotional symptoms,

the religious needs/resources, the hope and dignity related distress, through the following questionnaires validated in Italian language.

Edmonton symptom assessment scale

(ESAS) [17] validated in the Italian language [18]. We considered

the intensity of physical symptoms as moderate when the intensity

was from 4 to 6 of the numerical scale and severe when the intensity

was from 7 to 10 [18]. Moreover, moderate anxiety or depression

reported through the corresponding ESAS items (cutoff=4) has been

used as a screening tool for anxiety and depression [19].

System of belief inventory

(SBI-15R), developed by Holland [20], an instrument of selfcompilation,

consisting of 15 questions (items) which are grouped

in 2 sizes: the first consists of 10 items relating to religious beliefs

and practices, the second consists of 5 items, relating to the social

support provided by the religious community. The score of each item

consists of a four-level verbal scale ranging from "strongly disagree"

to "strongly agree" or "Never" to "Always". The SB-15R total score

ranges from 0 to 45, with higher values indicating higher levels of

religiousness. It was recently validated in the Italian version [21].

Herth hope index

(HHI) developed by Herth is a tool used to measure the cognitive,

affective, behavioral, temporal, and contextual dimensions of patients’

level of hope in a hospital setting [22]. HHI consists of 12 items on a

4-point Likert Scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly

agree). The scale has three subscales: inner sense of temporality and

future, inner positive readiness, and interconnectedness with self

and others. A high score on the HHI suggests that patients have

subsequently higher levels of hope. The HHI Italian version has been

validated with 266 patients, which had either solid or hematologic cancer during active oncological treatment and supportive care [23].

The results of the validation show the unidimensionality and the good

reliability indexes of the Italian version of HHI, and the practicality of

its use with cancer patients at non-advanced stages.

Patient dignity inventory (PDI)

Composed of 25 items to assess the dignity-related distress. Each

item was rated on a five-point scale (1. Not a problem; 2. A slight

problem; 3. A problem; 4. A major problem; 5. An overwhelming

problem). Five-point scales of this nature have been reported most

reliable on 6 measurements of attitude-judgment, with response

categories above five not yielding significant additional discrimination.

High PDI score is related to high dignity related distress [24]. The

Italian validation of PDI showed the one-dimensionality of the

instrument [25].

Statistical analysis

Usual univariate descriptive statistics are presented. To test the

differences between solid and haematologic cancer patients, chi square

or unpaired t test, according to the nature of the variable considered,

were performed. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. The

association of hope with the other collected variables, such as age, sex,

spirituality, psychological support, problems with dignity and phase

of disease was studied separately in the two groups of SC and HM,

through simple and multiple regression models. All the analyses were

performed using the statistical package STATA 12.1.

Table 3

Table 3

Crude and adjusted association, obtained through simple and multiple linear regression models, between hope (HHI score) and phase of disease, religious

needs/resources (SBI score), problems with dignity (PDI score), psychological support, sex and age class; stratified by type of cancer: Haematologic Malignancies

(HM) or Solid Cancer (SC). Regression coefficient and (95% C.I.).

Results

Table 1 shows clinical characteristics of patients with solid

(N=289) and haematological (N=169) malignances in different

phases of diseases. The patients had a mean age of 60 years (range 19-89), 47.9% were male. Most of the hematological patients were male

(55.9% vs. 43.2%; p-value=.009), and on average they were younger

than SC patients (57.8 vs. 61.1 years old, p=.012). The 70% of the

patients lived with the partner, 19% had a high level education. Most

of the patients were retired (47%), more often among SC patients

(50.7% vs. 41.4%, p=.043). Regarding religiousness, the 14% were

non believer, 45% believer and churchgoer, the rest believer non

churchgoer. In respect to patients with HM, SC patients received

more psychological support (29% vs. 18%, p=.007). Most of the

patients had KPS ≥80 (only 4.5% had KPS = 70). Half of the patients

were on active treatments (49%). Only 6.8% of all patients presented

relapse or metastases. Table 2 shows the percentage of patients with

physical and emotional symptoms of moderate to severe intensity

and the average score of religiosity, hope, and dignity related distress.

The 53% of the patients reported fatigue, 35% drowsiness, 26% pain,

25% anorexia, 13% nausea, 10% dyspnoea, 25% anxiety and 17%

depression, 29% sense of not well-being. We didn’t find any significant

differences between the two groups of patients about physical/

emotional symptoms. As concerns the religious resources, the SBI

score was higher in our sample among SC patients than among HM

patients (25.4 vs. 22.4 respectively, p =.036; max score=45), whereas

the levels of hope and dignity related distress (this last measured on

159 subjects only) were not significantly different in the two groups,

with an average score of 37 for hope (max score=48) and 50 for dignity

problems (max score=125). Table 3 Simple linear regression models,

fitted separately among SC or HM patients to show the association

between hope and selected covariates (phase of disease, age class, sex,

religious needs/resources score, problems with dignity, psychological

support), show interesting similarities between the two groups,

and some differential results. Whereas SC patients had higher hope

score (+2.4) at the entry in a treatment phase than at diagnosis, the

opposite (-3.5) occurred among HM patients. After adjustment for

the other covariates presented in table but PDI (due to collinearity),

the result was no more statistically significant among SC patients,

whereas among HM patients hope score was still significantly lower

(-3.3) during the treatment phase than at diagnosis, and in case of

relapse/metastases (-6.6). Age showed significant association with

hope among SC patients: people older than 65 years had a statistically

significant lower level of hope than those younger than 51 after

adjustments. Sex did show any association with hope neither at the

crude analysis nor after adjustment.

Religious needs/resources were positively associated with hope in

both groups of patients even after adjustment; the opposite (negative

association) was true for dignity related distress and psychological

support at the crude analysis only.

Discussion

Our study shows that fatigue, drowsiness, the sense of not wellbeing,

anorexia and pain of moderate to severe intensity were present

and overlapped in patients with solid cancer as well as in those with

hematological malignancies. Also the emotional symptoms like

anxiety and depression were similar among the two groups of patients.

However data of literature shows that the relief of pain and other

symptoms as psychological and spiritual suffering were frequently

under-recognized in patients with haematological malignancies

[26-28]. A recent review on psychosocial needs among patients who

received a diagnosis of cancer revealed that these aspects of suffering

were underestimated among HM patients in comparison with SC

patients [29]. HM patients fear of relapse, fear of death in a curative regimen, show specific social needs due to the change occurred in the

familiar system after the occurrence of the disease and information

needs as much as SC patients [28,29]. Preoccupation with death is a

predictor of psychological distress in patients with HM [30]. Among

HM survivors it has been shown high level of psychological distress

and financial worries, together with the perception of having their

own needs underestimated by health professionals [31]. The higher

psychological support received in our sample by SC patients may

be due also to the higher prevalence of female and of retired people,

given that women are more able to feel psychological needs and

retired people have more mental space to feel psychological needs

and more time to look for psychological support [32,33]. This result

strengthens the importance of giving more access to psychological

support for everyone after a cancer diagnosis and more attention

to communication processes in medical-patient relationships [34].

Patients who feel to be supported by good relationships with health

professionals tend to feel less need of specific psychological support,

as it has been shown in a recent study conducted in a Supportive

Care Unit [35]. We suggest that the decreased level of hope registered

among HM patients only, since diagnosis through the successive

phases of disease, might be due to the awareness of having a disease

spread all over the body, whereas SC patients after diagnosis more

easily feel that the disease is centered somewhere in their body, so

more controllable through targeted treatment. Anyway, these results

show again the importance of careful monitoring the psycho-social

needs among these patients. Depression and Hopelessness was

reported in leukaemia patients [15]. Moreover, in patients with

acute leukaemia (a highly fatal condition characterized by a sudden

onset and a fluctuating disease course) depression was associated

with greater physical burden while hopelessness, measured by Beck

Hopelessness Scale, was present in 8.5% of the patients and was

associated with older age and lower self-esteem. Both were associate

with poorer spiritual wellbeing [16]. SC patients had higher level of

spiritual/religious resources according to SBI. This might be related

to the smaller percentage (borderline statistically significant) of

SC patients that were non-believer and maybe also to the higher

proportion of SC patients who received psychological support.

Religiosity was positively associated with hope, with a similar force,

in the two groups of patients. Only few data are available on the hope

of patients with SC and HM on cure or follow-up, during supportive

care therapies to manage toxicities due to oncologic therapies, and

they confirm the positive association between religiosity and hope

[35]. Among SC patients older age was negatively associated with

hope. It has been shown that having long-term projects influences

positively hope [22], therefore it may be that older patients have lower

level of hope when facing a cancer disease just due to the feeling of

can no more have long-term projects in any way, both for the old age

and for the disease, whereas younger patients can still use the longer

life-expectation to keep having long-term projects and hope [27,30].

No data of the literature are available on the dignity- related distress

in patients on cure or follow-up during supportive care to manage

toxicities- related to oncologic treatments. In our study dignity-related

distress was negatively associated with hope in a similar way in the two

groups. The clinicians can use standardized questionnaires to assess

the dignity related distress [22] and the sense of hope [24] in cancer

patients during all phase the disease [23,25]. No cut-off is indicated

to the correct us of these questionnaires: the questions want more to

open a dialogue useful to make the patient feel safe and to trust health

professionals who know better what is really important for him/her

[36]. Indeed critical passages in the course of the disease can be dealt with better if this dialogue on important personal preferences and

values has already been opened. The multidimensional assessment

of cancer patients, on physical, psychological, social and spiritual

(including hope and dignity) dimensions, in any phase of the disease,

made by well-trained health professionals, gives them the possibility

to understand and to facilitate the dynamic process of coping with the

disease, and to find out which ways are still viable for wellbeing, even

in the presence of a life-threatening disease, by controlling symptoms

and giving relevance to personal hope and personal dignity issues

[37,38]. A number of studies indeed showed that patients involved

in decision-making processes on care have higher compliance with

the suggested treatments and better coping with the disease, resulting

in higher level of wellbeing [6,34,39,40]. The main limitation of this

study is its cross-sectional design which provides only weak support

to the hypothesized direction of the described association. Moreover

the differing setting of care of SC and HM patients makes the

comparisons open to different interpretations, and the national size

of the study makes its results to be confirmed in other health systems.

Overall the results of our study suggest the need for early

assessment and management of physical and emotional symptoms,

spiritual/religious needs, level of hope and dignity–related distress,

psychosocial support, also for cancer patients who are on cure or

follow-up [41]. SC and HM patients have overlapping physical and

emotional symptoms. However it is possible that HM patients need

to be more supported in order to encourage hope during the phase

of cure and relapse. According the data of literature, in comparison

with other kind of cancer HM seem to be less supported, for instance

there is a lack of self-help materials and of systematic provision

of information and support groups for patients, which may be

associated with lower empowerment among these patients [34]. The

early multidimensional assessment and the related early psychosocial

support can improve the skills of coping among patients and their

families, in order to manage the emotional reactions to disease and

treatments, and to integrate the disease’s experience into the life plan

both during active therapy and when the patient enters into follow-up

or rehabilitation settings of care [33,41].

References

- National cancer control programmes. Policies and managerial guidelines WHO .2002.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM), Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting, Board on Health Care Services in Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs (eds N.E. Adler and A.E.K. Page), The National Academies. Press, Washington, DC. 2008.

- Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Jacobsen PB, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle R, Butow PN. Psycho-Oncology, 2nd ed., New York. Oxford University Press. 2010.

- American Psychosocial Oncology Society in Quick Reference for Oncology Clinicians: The Psychiatric and Psychological Dimensions of Cancer Symptom Management (eds J.C. Holland, D.B. Greenberg and M.K. Hughes), IPOS Press, Charlottesville, VA. 2006.

- Lee SJ, Katona LJ, De Bono SE, Lewis K. Routine screening for psychological distress on an Australian inpatient haematology and oncology ward: impact on use of psychosocial services. Med J Aust. 2010; 193(5):74.

- Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, Christie G, Clifton D, Hill C, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy: the transformation of existential ambivalence into creative living while enhancing adherence to anti-cancer therapies. Psychooncology. 2004;13:755-68.

- Spiegel D, Classen C. Group therapy for cancer patients: a research-based handbook of psychosocial care. New York: Basic Books. 2000.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359 (9307):650-6.

- Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of effectiveness. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(10):692-700.

- Bonacchi A, Toccafondi A, Mambrini A, Cantore M, Muraca MG, Focardi F, et al. Complementary needs behind complementary therapies in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2015;24.

- Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA, Minasian LM, Basch E, Dueck AC, et al. A Literature synthesis of symptoms prevalence and severity in person receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Canc. 2013; 21:1525-50.

- Allart P, Soubeyran P, Cousson-Gélie F. Are psychosocial factors associated with quality of life in patients with haematological cancer? A critical review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2013;22(2):241-9.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160-74.

- Costantini M, Ripamonti C, Beccaro M, Montella M, Borgia P, Casella C. Prevalence distress, management and relief of pain during the last 3 months of cancer patients’ life. Results of an Italian mortality follow-back survey. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:729-35.

- Morselli M, Bandieri E, Zanin R, Buonaccorso L, D'Amico R, Forghieri F, et al. Pain and emotional distress in leukemia patients at diagnosis. Leuk Res. 2010;34(2):e67-8.

- Gheihman G, Zimmermann C, Deckert A, Fitzgerald P, Mischitelle A, Rydall A, et al. Depression and hopelessness in patients with acute leukemia: the psychological impact of an acute and life-threatening disorder. Psychooncology 2016;25(8):979-89.

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9.

- Moro C, Brunelli C, Miccinesi G, Fallai M, Morino P, Piazza M, et al. Edmonton symptom assessment scale: Italian validation in two palliative care settings. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(1):30-7.

- Ripamonti CI, Bandieri E, Pessi MA, Maruelli A, Buonaccorso L, Miccinesi G. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) as a screening tool for depression and anxiety in non-advanced patients with solid or haematological malignancies on cure or follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(3):783-93.

- Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psychooncology. 1998;7(6):460-9.

- Ripamonti CI, Borreani C, Maruelli A, Proserpio T, Pessi MA, Miccinesi G. System of belief inventory (SBI-15R): a validation study in Italian cancer patients on oncological, rehabilitation, psychological and supportive care settings. Tumori. 2010;96 (6):1016-21.

- Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17(10):1251-9.

- Ripamonti CI, Buonaccorso L, Maruelli A, Bandieri E, Boldini S, Pessi MA, et al. Hope Herth Index (HHI): a validation study in Italian patients with solid and hematological malignancies on active oncological treatment. Tumori. 2012; 98: 385-92.

- Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, Hack T, Kristjanson LJ, Harlos M, et al. The Patient Dignity Inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(6):559-71.

- Ripamonti CI, Buonaccorso L, Maruelli A, Bandieri E, Pessi MA, Boldini S, et al. Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI) questionnaire: the validation study in Italian patients with solid and hematological cancers on active oncological treatments. Tumori. 2012;98(4):491-500.

- Bandieri E, Sichetti D, Luppi M, Di Biagio K, Ripamonti C, Tognoni G, et al. Is pain in haematological malignancies under-recognised? The results from Italian ECAD-O survey. Leukemia Research.2010;34: e334-5.

- Wittmann M, Vollmer T, Schweiger C, Hiddemann W. The relation between experience of time and psychological distress in patients with haematological malignancies. Palliat Support Care.2006;4(4):357-63.

- Priscilla D, Hamidin A, Azhar MZ, Noorjan KO, Salmiah MS, Bahariah K. Assessment of depression and anxiety in haematological cancer patients and their relationship with quality of life. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2011;21(3):108-14.

- Swash B, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1131-41.

- Vollmer TC, Wittmann M, Schweiger C, Hiddemann W. Preoccupation with death as predictor of psychological distress in patients with haematologic malignancies. Eur J Cancer.2011;20:403-1.

- Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher RW, Lynagh MC, Tzelepis F, D’este C. What do haematological cancer survivors want help with? A cross-sectional investigation of unmet supportive care needs. BMC Res Notes.2015;8: 221.

- Merckaert I, Libert Y, Messin S, Milani M, Slachmuylder JL, Razavi D. Cancer patients' desire for psychological support: prevalence and implications for screening patients' psychological needs. Psychooncology.2010;19(2):141-9.

- McGrath PD, Hartigan B, Holewa H, Skarparis M. Returning to work after treatment for haematological cancer: findings from Australia. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):1957-64.

- Ernst J, Berger S, Weißflog G, Schroeder C, Koerner A, Niederwieser D, et al. Patient participation in the medical decision-making process in haemato-oncology-a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013; 22(5):684-90.

- Ripamonti CI, Miccinesi G, Pessi MA, Di Pede P, Ferrari M. Is it possible to encourage hope in non-advanced cancer patients? We must try. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(3):513-9.

- Chochinov HM, McClement SE, Hack TF, McKeen NA, Rach AM, Gagnon P, et al. The Patient Dignity Inventory: applications in the oncology setting. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(9):998-1005.

- McClement SE, Chochinov HM. Hope in advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1169-74.

- Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, Thompson G, Dufault B, Harlos. Eliciting Personhood Within Clinical Practice: Effects on Patients, Families and Health Care Providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015; 49(6):974-80.e2.

- Watson M, Kissane D. Handbook of psychotherapy in cancer care. Chichester; John Wiley & Sons. 2011.

- Moorey S, Greer S. Cognitive behavior therapy for people with cancer. 2nd ed. New York; Oxford University Press. 2006.

- Chochinov HM. Dignity in care: time to take action. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):756-9.